Text excerpted from UpToDate.

Indications

Evaluation of new onset ascites.

Testing of ascitic fluid in a patient with preexisting ascites who is admitted to the hospital, regardless of the reason for admission.

Evaluation of a patient with ascites who has signs of clinical deterioration, such as fever, abdominal pain/tenderness, hepatic encephalopathy, peripheral leukocytosis, deterioration in renal function, or metabolic acidosis.

Relative contraindications

The benefits of abdominal paracentesis in patients with appropriate indications almost always outweigh the risks. An analysis of the fluid helps determine the cause(s) of the ascites and the likelihood of bacterial infection, and it can identify antibiotic susceptibility of any organisms that are cultured.

However, there are some relative contraindications to paracentesis:

Patients with clinically apparent disseminated intravascular coagulation and oozing from needle sticks. This occurs in <1/1000 patients with ascites in our experience. Paracentesis can be performed once the bleeding risk is reduced by administering platelets and, in some cases, fresh frozen plasma.

Primary fibrinolysis (which should be suspected in patients with large, three-dimensional bruises). Paracentesis can be performed once the bleeding risk is reduced with treatment.

Paracentesis should not be performed in patients with a massive ileus with bowel distension unless the procedure is image-guided to ensure that the bowel is not entered.

The location of the paracentesis should be modified in patients with surgical scars so that the needle is inserted several centimeters away from the scar. Surgical scars are associated with tethering of the bowel to the abdominal wall, increasing the risk of bowel perforation.

An elevated international normalized ratio (INR) or thrombocytopenia is not a contraindication to paracentesis, and in most patients there is no need to transfuse fresh frozen plasma or platelets prior to the procedure. Seventy percent of patients with ascites have an abnormal prothrombin time, but the actual risk of bleeding following paracentesis is very low (less than 1 percent of patients require transfusion).

Setup

Patient preparation consists of explaining the procedure to the patient and obtaining informed consent. Patients do not need to be fasting before the procedure.

Equipment

- Signed consent form

- Ultrasound machine if needed to localize the entry site

- Completed lab slips and labels

- Red-top tube, purple-top (EDTA) tube, blood culture bottles (2)

- 1- to 2-liter vacuum bottles (for therapeutic paracentesis, enough bottles to remove 8 L of fluid should be available)

- Iodine or chlorhexidine

- Alcohol wipes (3)

- Sterile 4x4 gauze sponges (2)

- Sterile and nonsterile gloves

- Sterile syringes (3, 5, and 20 mL)

- Skin anesthesia needles (25- or 27-gauge 1.5 inch needle, or a tuberculin syringe plus, an 18-gauge 1 to 1.5 inch needle and a 22-gauge 1.5 or 3.5 inch needle) (see 'Anesthetizing using a Z-track technique' below)

- Paracentesis needles

- 18-gauge needles for inoculating blood culture bottles and specimen tubes (2 or 3)

- #11 blade scalpel (for therapeutic paracentesis)

- Lidocaine, 1 percent

- Adhesive bandage

- Sharp receptacle box

Generally, gowns, caps, and sterile drapes are not required for this procedure--only sterile gloves and technique when anesthetizing and introducing the needle.

Technique

Patient position

Paracentesis is usually performed with the patient supine. The bed or gurney is either flat, or the head is slightly elevated. Rarely, the patient can be positioned prone on "all fours" or spanning two gurneys. This position is used only when there is a small amount of fluid and making a diagnosis is crucial to the patient's management (eg, tuberculous peritonitis). The face-down position with the fluid pooled in the dependent abdomen permits drainage of the last few milliliters of fluid.

Selecting needle entry site

Paracentesis is typically performed through the abdominal wall in the left lower quadrant. In the midline cephalad or caudad to the umbilicus, abdominal wall collateral vessels may be present, so those areas that should be avoided. Surgical scars and visible veins should also be avoided. Surgical scars may be associated with bowel that it tethered to the abdominal wall by adhesions, thus putting the patient at risk for bowel injury if the paracentesis is performed near a scar.

When choosing a site, it is useful to confirm that there is dullness to percussion, that the spleen is not palpable, and that there are no surgical scars within several centimeters of the intended entry site. If there is uncertainty, ultrasound can be used to further confirm the presence of fluid and the absence of bowel or the spleen within range of the needle.

Skin sterilization

Once we have chosen a site, we place an "X" at the site using an ink pen and then make marks at positions 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock, a few centimeters from the central "X." We sterilize the skin at and around the "X" with iodine or chlorhexidine, which removes the original "X." However, the original position of the "X" will be at the center of the four marks.

Wearing nonsterile gloves, the operator cleans the selected needle entry site with iodine or chlorhexidine solution using widening circular motions starting at the "X."

Anesthetizing

We then put on sterile gloves and draw up a 1 percent lidocaine solution into a sterile 3 to 5 mL syringe.

The ideal needle for administering lidocaine to anesthetize the skin is a 1.5 inch 25- to 27-gauge needle, since it is usually sufficiently long to deliver anesthetic throughout the intended paracentesis track, except in the obese patient. An 18-gauge needle can be used to draw up the lidocaine into a 3 to 5 mL syringe. That needle can then be removed, and the 25- to 27-gauge needle placed on the syringe.

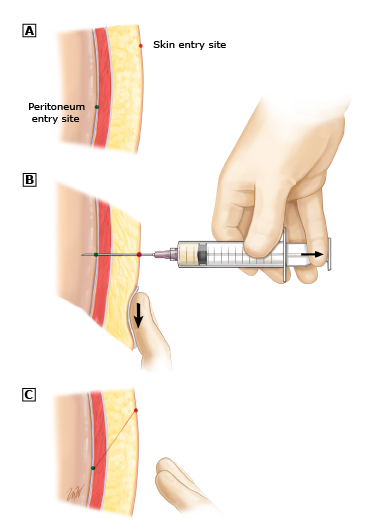

The skin can then be anesthetized by approaching the chosen entry site tangentially with the needle and raising a wheal. Once the wheal has been raised, the needle is withdrawn and placed at the entry site perpendicular to the curve of the abdominal wall. Using a Z-track technique, 3 to 5 mL of lidocaine is used to anesthetize the entire soft tissue tract. The Z-track creates a non-linear pathway between the skin and the ascitic fluid, thereby helping to minimize the chance of an ascitic fluid leak.

A: Relative locations where the needle will enter the skin and the peritoneal cavity. B: The skin is pulled down, and the needle is then advanced in 5 mm increments, pulling the plunger back a few millimeters with each advancement to see if any blood or ascitic fluid is aspirated. C: The skin is released, returning the skin and peritoneal cavity entry sites to their original positions.

The needle and attached syringe are inserted in 5 mm increments. Then the plunger should be pulled back a few millimeters with each advancement to see if any blood is aspirated. If no blood is evident, a small amount of anesthetic is injected, and the needle advanced another 5 mm. This process is continued until the needle enters the ascitic fluid. As the needle is advanced, aspiration should be intermittent, not continuous. (Continuous aspiration may pull bowel or omentum onto the needle tip as soon as it enters the peritoneal cavity, occluding the tip.)

Paracentesis needle insertion

The paracentesis needle should be inserted along the pathway that was anesthetized. The paracentesis needle is also inserted using a Z-track technique. If a 15- or 16-gauge needle is being used for a therapeutic paracentesis, a #11 blade scalpel nick in the skin will be required to permit insertion of the needle. This tiny nick should be just long enough to permit the entry of the needle. The larger the nick, the higher the likelihood of a post-paracentesis leak.

Once the paracentesis needle has entered the peritoneal cavity and fluid is aspirated, the hand that is on the abdominal wall can be removed to assist with further maneuvers. The depth of entry of the needle must be stabilized so that it does not pull out of the peritoneal cavity. If the skin has been properly held on the abdominal wall during needle insertion, fluid should drip from the hub of the needle once the syringe is removed. This proves that the needle is still in good position.

Initiating flow

Sometimes there is a flow of a few drops of fluid, and then the flow ceases. This may be due to a narrow plane of fluid, with bowel or omentum occluding of the needle tip. The patient can be slowly and gently repositioned to pool more fluid in the vicinity of the needle. This will usually reestablish the flow of fluid. In some cases, the operator has inadvertently allowed the needle tip to pull out of the peritoneal cavity, back into the abdominal wall. If this occurs, the needle can be inserted further in an attempt to reestablish the flow of fluid.

Obtaining fluid for testing

IV tubing with a vacutainer can be attached to the needle to ease drawing of fluid into tubes for lab testing. Usually approximately 25 mL of fluid are needed for a cell count, differential, chemical testing, and bacterial cultures. Usually a purple-top (EDTA) tube is drawn first for cell count + differential, then yellow top for chemical tests, and then blood culture bottles (aerobic and anaerobic).

Removing large volumes of fluid

A large-volume paracentesis has been defined as the removal of >5 liters of ascitic fluid. Patients with tense ascites should have enough fluid removed to relieve the intra-abdominal pressure in order to make the patient comfortable and to minimize the chance of a leak of ascitic fluid. If a patient is known to have refractory ascites, the removal of as much fluid as possible will extend the interval to the next paracentesis.

An 14G angiocath plus IV tubing can be used for rapid drainage of ascitic fluid into 3L orange bottles.

Needle removal

Once it has been determined that no further fluid is needed, the needle should removed in one rapid, smooth withdrawal motion. We have found that it is helpful to distract patients by asking them to cough as the needle is removed. The cough seems to prevent the patients from sensing pain during removal of the needle.

The paracentesis site can then be covered with a bandage of sterile gauze covered with a Tegaderm.

Complications

Ascitic fluid leak

The most common complication following paracentesis is an ascitic fluid leak, which occurred in 5 percent of patients in one study. Leaks typically arise when a Z-track has not been performed properly, a large-bore needle has been used, and/or a large skin incision has been created. We have rarely encountered a leak using the technique described above.

When a leak occurs, placing an ostomy bag over the leak site allows quantitation of the amount of fluid that is leaking. Placing gauze dressings over the site usually leads to rapid soaking of the dressings, rapid dressing changes, and maceration of the skin. Usually the amount of fluid decreases over a period of a few days if the patient is diuretic-sensitive. If the fluid is refractory to diuretic therapy, another therapeutic paracentesis may need to be performed (using proper technique) to stop the leak. Cellulitis may develop in the skin near the leak if it is prolonged. Retrograde infection of the ascitic fluid is exceedingly rare. If there is a large scalpel incision at the site, it can be sutured. However, the fluid may then dissect into the underlying soft tissue.

Bleeding

Bleeding from an artery or vein that is impaled by the needle can be severe and potentially fatal. An external figure-of-eight suture can be placed surrounding the needle entry site if the inferior epigastric artery is bleeding. Rarely, a laparotomy is required to control the hemorrhage. The risk of serious bleeding appears to be higher if renal failure is present. Patients with primary fibrinolysis may develop three-dimensional hematomas and require antifibrinolytic treatment.

Bowel perforation and infection

Infection is rare unless the bowel is entered by the paracentesis needle. Bowel perforation by the paracentesis needle occurs in approximately 6/1000 taps. Fortunately, it usually does not lead to clinical peritonitis and is generally well tolerated. Treatment is not required unless patients develop signs of infection (eg, fever, abdominal tenderness).

Mortality

Death due to paracentesis is exceedingly rare (zero in most series). In the two largest series, there were a total of nine deaths out of 5244 procedures (mortality rate 0.16 to 0.39 percent). Eight of the deaths were due to bleeding, and one was due to infection.